Theology Department

St. Stephen's

Episcopal School

Austin, Texas

Tradition

-the episcopal church

Curriculum

-theology 12

-theology 8

-theology senior elective

Resources

-books

-community service

-ethics

-human rights, interfaith

dialogue, & peacemaking

-environmental concerns

-historical figures

-larger perspectives

-practice

Contact

please report invalid links to: theology@sstx.org

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

For more background on Eliade and his ideas, check:

Here for a brief introduction with several interesting links.

Here for more information, a good bibliography, and more.

Examples of the attention paid by homo religiosus to the sky are evident here.

Review by Chapter (scroll down)

Introduction and Review of Chapter 1, The Sacred and the Profane

Who was Mircea Eliade?

Mircea Eliade was a native of Rumania who devoted his life to studying

universal patterns in religion as a teacher at the University of Chicago.

While Rudolph Otto was interested in describing the nature of the numinous

(religious) experience and the human (particularly psychological) responses,

Eliade was interested in what people do-- how they structure their

physical space, the flow of time, their attitudes toward nature and women,

toward one another, and toward even the most mundane things. Where Otto

was concerned with the non-rational aspect of the religious experience,

Eliade was more concerned with the rational manifestations of

the spiritual impulse -- words, behavior, objects, thoughts, and the

connecting patterns he found.

Otto noted that people were seized, or confronted, by an "unnamed Something," a Mystery. He suggests such experiences are not a matter of choice. While others would argue that last point, Eliade seems to agree. "The Sacred" manifests itself. This is called a hierophany -- something Sacred shows itself to an individual or a group. If a hierophany involves a specific god, it is a theophany. Examples run throughout the Bible -- God with Adam and Eve, with Noah, with Abraham, with Jacob, with Moses during the Exodus, the moment on Sinai, the conquest of Canaan, from the birth of Christ to the resurrection and in its aftermath. For Muslims, the appearance of Allah in Mohammed's life. All are hierophanies -- in these cases, theophanies of a specific god, events within what became the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim traditions, with many variations.

Eliade notes we can view the history of religions as a series of hierophanies --

reality-shattering moments in which the Sacred bursts through ordinary

humdrum existence, changing those involved. People thought things were

one way. They learn otherwise.

Siddhartha by the river.

The saint Narada's experience after asking Vishnu

to show him his maya.

The burning bush and Moses.

John the Baptist, concluding that the one he baptizes in a river one day is

special, a human link to something transcendent.

The women who went to the tomb, found it empty, and fled, astonished.

Saul on the road to Damascus, and in an instant finding himself and history

changed.

Mohammed being called to be the Prophet.

The Buddha sitting beneath the bodhi tree, committed to gaining understanding.

In each case, what they thought was real was not the whole story -- their ontological orientation was called into question. They came to a more complete understanding. A vision was glimpsed. Perhaps all that had come before is then thought of as a dream. Or a component of a far more complex reality. They see something; in wonder, they spend their lives responding to that experience, as in some cases do their friends, children, grandchildren, and on. Their responses form the pattern in which Eliade is interested. And the worst thing that can happen for these people -- homo religiosus -- is that they forget -- that they lose that sustaining vision of what is really real, of what matters most.

For Eliade, these events -- these hierophanies -- shape attitudes, cultures, art, architecture, literature, war, gender roles, history. The shared understanding of being driven in some way by the hierophany of one's ancestors is so powerful that it is carried forward through history, even thriving while those adhering to this understanding think and talk and argue about exactly what it all means.

Homo religiosus, including members of a tradition, live in a sacralized world. The world is recognized as a creation which reflects its sacred source. The people have an understanding, however provisional, of what lasts, what is permanent, what is most real. In the purest form as described by Eliade, they belong to a traditional society, strive to live in a sacred universe, to live a life that is saturated with meaning. They live in a cosmos -- an orderly place that makes sense. Their spaces -- home, village, town, country -- have structure, form, a connection to the Sacred. The way they organize time has a similar form and structure. Their attitudes, he implies, are notable for depth, consistency, integrity. They see that there are some places and some times that are qualitatively different from others because they make possible communication with the Sacred. Christmas. Yom Kippur. The Fall Equinox. The Summer Solstice. Harvest time. Planting time. Rosh Hashanah. Easter. Spaces and times are not all the same -- they are not homogeneous. Some places, some times, seem to be saturated with meaning and power for these folks. The most sacred place is where a hierophany took place, and the reproductions of that place in the form of temples, churches, mosques, or in even smaller versions like crosses, stars, etc., all over the world, reproducing the place where the event happened. The most sacred time is the time of year, month, week, day, hour, moment that the Sacred burst through. Loaded with power, these places and times attract religious people. People in the "sacred mode of being" gravitate toward these places and times (as in a pilgrimage), seeking access, a refreshing of the awareness and clarity that has worn away. Such a person has an appetite for meaning, for knowledge, for understanding, for affirming the life they are leading. If this ontological thirst is quenched; the satisfaction and clarity can last a long time. Never lost, because they always remember -- who they are, where they came from, the wonder of their own existence, of the world around them.

The extreme alternative to living in a sacralized world, Eliade says, is profane existence -- a life lived in spiritual chaos, in which all times and spaces are the same -- homogeneous. Think of when we have been really, truly, literally, lost. There are no fixed points, no way to get one's bearings, physically or spiritually. One is adrift in a world of relativity and subjectivity, in which there is nothing absolute, no landmarks, no way to discover where we are, to tell right from wrong in a way that has any depth to it. It is an existence that is completely secular (untouched by, and uninterested in, the Sacred). It denies the possibility of something transcendent. From the viewpoint of homo religiosus, such a person is a tragic figure living in a desacralized world from which the sacred aspect has been drained just as blood can be drained from a body. What is left is a lifeless shell, lacking in spirit or meaning. And yet, Eliade says, as the shell remains; there is an echo of an older way -- from the perspective of homo religiosus, a more substantial & nourishing way to live. The form carries on in camouflaged ways, but the substance has leaked out. Always the fun-loving prankster, Eliade says most modern Westerners (that's us) live in the profane mode of being. He implies such a person lives a hollow existence in a fragmented world, where life is either utterly meaningless or whatever meaning is found is cobbled together in a temporary, fragile construction. Often unaware of the emptiness of their lives, he suggests that when people in the profane mode of being become aware of that emptiness, interesting things can happen.

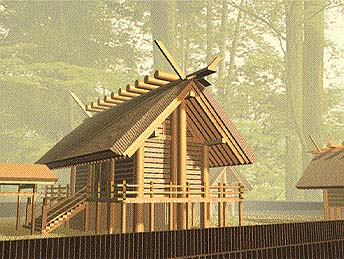

On the other hand, for homo religiosus, living in the "sacred mode of existence," a hierophany has irrupted in an otherwise homogeneous space, changing it forever, creating a "fixed point." This is the Center of the World, often marked by an axis mundi or "cosmic pillar." It can be a tribe's special pole, the Black Hills, Mt. Sinai, the cross, the bodhi tree for Buddhists, Mt. Mehru. A vertical break in space, it reaches up and down, connecting heaven-earth-underworld, marking the Center, providing a fixed point for orientation, enabling communication with the divine. Outward from this center stretches a "cosmic image," an imago mundi, often in the four cardinal directions, which represents a microcosm of the entire creation. You might think of the axis mundi as both a landmark and an antennae, helping sending out signals, and pulling others in.

The Center can be reproduced infinitely. For a Christian, Eliade suggests wherever the cross is carried or found marks the Center. Sometimes a special place is designated by a sign -- something less than a full-blown hierophany, but enough to indicate the sacredness of a particular place. On the one hand, Eliade seems to say that people cannot choose a sacred site. But they can seek it and find it with the help of such signs. On the other hand, he notes that if a religious person or group occupies new territory, they consecrate it -- repeating the acts of the gods in the original creation, claiming and structuring this new space in a way consistent with their beliefs.

The Center is arrived at by passing through a threshold. The steps and doorway of a church, temple, mosque, being examples. The threshold marks the boundary between two worlds; a passageway from the profane to the sacred. One leaves one kind of space for something very different, simply by approaching and stepping inside or outside. A threshold can open upward; think of the axis mundi this way, too.

Religious man wants to live at the Center, where heaven, earth, and underworld are linked, where communication is possible, where life is secure and full of meaning. Living close to the Center means living close to the Sacred. The further one travels from the Center, the closer one is to Chaos. The truest, purest, strongest world is at the Center. The Temple in Jerusalem is a Center, surrounded by the imago mundi of Jerusalem and Israel, earthly representations of a transcendent model. And the Temple itself plays a role in resanctifying the world. It is a conduit of the Sacred. A source, a reservoir, a wellspring, near which one lives, to which one returns.

In an interesting tangent, Eliade says the creative process is implicitly spiritual:

"Every construction or fabrication has the cosmogony as paradigmatic model"

The creation of the universe is imitated in every creative act, a concentration of what is real, lasting, permanent, sacred. Suggesting, perhaps, that a person engaged in creating things is in some sense in touch with "the Sacred."

Eliade is focusing particularly on the building of a town or a specific structure, centered on a particular point, and stretching out, usually in the four cardinal directions, with a square or a hub in the middle. How far can you push his idea?

The human home is a microcosm of what has happened to society. In a traditional religious society, the home is always sanctified. There is a central point, sometimes a fire place. The four directions are referred to somehow. Attention is paid to the direction in which a door faces, & to having an opening upward. An animal is sacrificed, transferring life and soul to the structure.

Deciding where to live is of enormous importance. We create our own world, maintain it, renew it. The house is a universe unto itself, built by a human being who is imitating the work of the gods when they created the cosmos.

Review of Chapter 2, The Sacred and the Profane

Think about the fact that religion begins and ends with "the eternal." Is there something that has always existed, and will always exist? Most religions tend to say "yes," and then try to understand our particular moments, our history, in relation to that mind-bending idea of "eternity." In other words, they try to make sense of the flow of time we experience second-by-second for the length of our lives in relation to the seemingly separate phenomenon of eternity.

Does homo religiosus think "ordinary time" was invented at the creation? If there was a moment of creation, what existed before that? Before the material world came into being, was there such a thing as time? A hearty crunchy breakfast question for the religious and unreligious alike.

Moving right along, one of the interesting things that a religion tries to do is focus on, and work through, the fact that "time" is both the context of reality and the content of reality. Let's try that again. Time refers to the eternal, unchanging temporal environment of our existence and also to the momentary, ever-changing mode of expression of our existence. Like science, religion identifies different stages of "relative time." Unlike science, religion tries to understand the connection between relative temporal stages and timeless eternity itself.

Remember: we're not confused. We will keep going.

Think of the story Wendy Doniger told about Markandeya living his happy life, until one day he fell out of the mouth of god. There he stood, staring at the sleeping Vishnu, in whose body his whole life had taken place, and in whose body his whole world, in fact, existed. Enough of a shock to prompt a mild headache; certainly justification for an excused absence from school. In the end, Markandeya climbs back in Vishnu's mouth and lives his life -- it's what he has to do. It's what Vishnu wants him to do. And the alternatives don't seem to be particularly numerous or enjoyable. He goes back to his life, but he will remember.....imagine Markandeya on the late-night shopping run to the Circle K, walking down the aisle, occasionally flashing on that strange somersault he took that day way back when, when he landed in a strange place and stared up at gigantic Vishnu snoring up a storm and occasionally spilling the odd innocent civilian out his mouth. Making sense of one familiar world, and spending a lifetime remembering that brief glimpse of a larger, more complete world.

Remember that Eliade says that for religious women and men, there are

two kinds of space -- sacred & profane. The same holds for time.

Some times are particularly powerful. These times offer access to

a particular state of mind in which life makes sense, has meaning, and

is connected to something transcendent and eternal. Even religious people

can forget such things if they're not careful. Thus the necessity of

remembering, for homo religiosus -- taking care to touch base,

to do those things that remind them of who they are, what their tradition

is, what has value, lest they forget.

Eliade identifies four kinds of time: mythical, historical, sacred, and festival. Festival

times (including Christmas and Easter) seem to serve the same purpose regarding

time that a doorway serves regarding space. Maybe a festival is a threshold into

a different state of mind -- a different, powerful time. A festival enables

religious folks to pass from ordinary, mundane, "profane" time into

a special, extraordinary, "sacred" time. In doing so, they remember

what is most fundamentally important.

Mythical time seems to refer mainly to pre-Christian traditions

(72), emphasizing stories of non-historic events, and which usually relate

to creation -- "the beginning," before which nothing, including time

itself, existed. Eliade seems to think this idea does not apply very well to

Christianity; for Christians, Jesus is God incarnate, acting in history, and

thus historical time is sanctified. What do you think? On the other hand, Mythical

time seems to refer to the time, accessible and always present tense, in

which God or the gods have always been, and will always be, active. The stories

people tell about God or the gods are myths (true stories, or True stories,

in some sense). When people gather in a special sacred place at a special sacred

time of the year and recite these stories, they are reading, thinking, reciting

aloud, and remembering. Are they talking about mythical time? It seems

to depend on the tradition, Eliade says. But mythical time or not, he says

they have reactualized a sacred event that took place "in the beginning." They

have stepped out of humdrum daily existence and into a richer, deeper, fuller

existence. They are no longer stuck in ordinary "profane" time, but

have made "primordial mythical time" present by these simple

acts. They have tapped into a state of mind, a "time," that provides

meaning, direction, purpose, understanding, and quality to their existence.

They have recreated a "Sacred time."

So, Sacred time seems to refer to a time that is always there, ready

to be recreated and tapped into. We might think of it as a refreshing, renewing

source, to which homo religiosus can return. A time when things are

clear, not confused; pure, not corrupted; abundant and fresh, not exhausted

and worn out. Sacred time is created when religious people gather to re-orient

themselves, to remember, and to begin again.

What does it mean to say that sacred time is eternally present? There

are a few ways to think about it. We read about religious people celebrating

the New Year because time, and the world, have worn out. Things are spinning

out of control, becoming chaotic, and there is an annual urgent need to start

over -- to reclaim a state of mind and a time when things are new and full

of possibilities. Again, this happens by tapping into sacred time, the rejuvenating

Source that never runs out, changes, or winds down. It gives hope, a clean

slate, to begin anew. "Things could be that good again. Let's try again,

and start over." If God or the gods are eternal and unchanging, then perhaps

they are the only things that do not change. They are static, permanent, and

for them there is no past or present. They've always been there, and always

will be. Thus their time is always present-tense. To reconnect with God or

the gods, as people all over the world do through prayer, meditation, liturgy,

etc., is to become contemporary with them, to step out of the

flow of historical time, and to step into a perspective, a time, that

does not flow, change, or move. That time is fixed and constant, always there,

while everything else is in flux.

Regarding Annual Repetition of the Creation, it seems that for religious

people there is no "last chance." The possibility of change,

redemption, getting straight, cutting through the fog, clearing away the clutter,

thinking in a way that is good and strong and beneficial, is a possibility

that never goes away. Think about the various stories we've read and discussed.

Creation is the result of chaos giving way to a structured, orderly

existence -- cosmos. Space and time are created, and take coherent shape.

Very frequently water (or a dragon/serpent) figures into the discussion,

as a symbol of chaos (e.g., Genesis 1, the Flood, the Red Sea, crossing

over the River Jordan into the Promised Land). When religious people tell stories

about the creation, our friend Eliade says they are not simply commemorating

it. They are in fact repeating the creation. It's an annual repetition

of the cosmogony, the creation of the cosmos. It's a way of regenerating time,

oneself, the tribe, the society. It is a symbolic rebirth. A year winds

down into chaos. The world itself seems to be spinning out of control. The

need to annihilate this unhappy existence is urgent and clear. Reciting a relevant

story or performing a ritual devoted in part to such stories seems to be part

of this idea -- erasing what was, purifying existence anew, regenerating that

wonderful time at the beginning of things, starting over again. Eliade says

religious people seem to know that things can be better than they are. There

was a time when things were good. This memory haunts religious people, who

intuit that there was a marvelous time in which life made sense, was plentiful,

and allowed all creatures and the gods to be at their strongest, at a creative

peak.

The idea of Myth as Paradigmatic Model is

that by "doing

what the gods did," religious people continue to live "in the

sacred" -- their life is real, not illusory, and has spiritual meaning,

not simply a complex set of biological and psychological needs to be

filled that can be dressed up as meaningful but are ultimately all about

survival. It's only by paying attention to stories about what God or

the gods did, and imitating them, that homo religiosus becomes

complete. Without such an understanding and behavior, they are hollow,

Eliade seems to suggest, shells of what they could be.

So, just as religious people want to be physically close to the Sacred

by going to a special place where communication is more likely to happen,

they also want to be close in time. Some days or seasons offer better

access than others. Returning to this source of the Sacred rescues life from

meaninglessness; the fact that they return periodically suggests that the quest

for meaning is an ongoing struggle or affair. And note what Eliade suggests

about those who are non-religious, yet whose lives, including significant and

meaningful (but still profane) times, are in some cases marked by the repetition

of words and acts in which they do not believe. Eliade implies that from the

perspective of a religious woman or man, such an existence is grim.

Review of Chapter 3, The Sacred & the Profane

The connection between nature and religion is the focus of Chapter 3. For homo religiosus, the world is a creation of the divine. It follows that Nature is connected to the supernatural. Eliade argues that the world's very structure seems intended to evoke within homo religiosus an awareness of that connection. It virtually forces us to look up, to the sky. Walk around St. Stephen's and note how often you can see as much or more of the sky as you can of the earth. Reflect on Ch. 1, and how the verticality of a space means everything. Think about the expensive extremes people went to (and still go to) to build amazing towering churches, temples, shrines -- often impractical with regard to seating, lighting, heating, acoustics, etc., but practical and productive if the purpose is to trigger a certain response as we feel and see the space around us. Perhaps they weren't doing this to provide employment for the craftsmen, engineers, and architects, or as an expression of the vanity of the rich and powerful. What other agendas, perhaps subconscious, can we identify?

Other thoughts: The main room at the local Hindu temple -- Barsana Dham (on your way to the Salt Lick restaurant) -- features a large high ceiling painted like the sky. Eliade points out the the sky is the ultimate expression of an idea; it is the paradigmatic image of transcendence. The universe is understood to be transparent, as opposed to opaque. It allows one to see through it to something else. Expand the idea. Consider the world we walk through every day and rarely stop to observe closely. Consider it as homo religiosus does: a lens through which we can glimpse the Sacred, a speaker through which we can hear the Sacred, a wealth of textures offering tactile apprehension, an abundance of smells and flavors that can overwhelm us. Our fun-loving author seems to suggest that by adjusting the antennae correctly, we can pick up the signals of the Sacred from the natural world, starting with our natural selves. Yoga, prayer, meditation, church, temple, walking, breathing, singing, eating, exercising, etc., can be more than what they seem to be at face value. They can be ways we adjust, sorting out the static, in order to pick up the signals clearly. Ideas to note:

Modalities of the sacred Perhaps with this phrase Eliade is saying that the feeling experienced by homo religiosus can vary in intensity, expression, clarity, and so on. A tangent: different people experience "beauty" differently (think of a horse running, the desert blooming after an intense storm, a cello's voice brought out by an accomplished player, an old person with a lively, generous spirit). The same thing might be said of "the Sacred" -- it manifests itself in different ways, places, times, degrees, intensities. The medium changes; the core message is the same. The modalities -- the way in which the Sacred is transmitted, apprehended, etc. -- come in many varieties.

Ontophany and hierophany Hang on here, campers. We've talked around the issue of how a person engaged in a creative act always reveals something personal (the way they work with teammates, play on a keyboard, move a pen on paper, shape clay, cook, dance, etc., always reveals something of who they were at the moment they were engaged with such creative work). So, maybe, what is created reflects something of its creator. If the world -- including its laws (gravity, thermodynamics, etc.) and rhythms that express themselves within it (seasons, tides, moon) -- are creations of God or the gods, this is the "cosmos" about which we've read. Order and balance are reflected in the world, not just through what we see or hear but in the way it works -- through its laws and rhythms as well. Nature and its principles will not go away. The particular living things within Creation will endlessly reproduce -- they will be fruitful and multiply exuberantly, in an annual, powerful show of fertility. Millions of acorns. Birds migrating. The wind rippling miles of grass and carrying seeds a long way. Some say all of this "just is," with its own meaning, available to those paying attention. Nature serves as a manifestation of reality, of "what is," or "being," or what is "real" (ontophany) as well as a manifestation of the sacred (hierophany), for homo religiosus.

The Celestial and Uranian Gods The sky, reflecting infinite transcendence, is naturally connected with the notion of the gods. Examples? Check out Exodus and the Psalms for starters. The sky arouses a sense of divine transcendence. The celestial god lives there and uses its instruments -- thunder, lightning, storms, meteors, clouds etc. -- to manifest itself. Confronting the sky, homo religiosus is struck by the enormity of the divine and the limited sphere in which human beings live and move. Humility would seem to be a natural response, as would Otto's ideas of majestas and tremendum (depending on the weather......).

The Remote God Again, a common pattern in religious traditions is that of the "god in the sky," who is almost always male. He withdraws, fatigued by the act of creation, becomes remote, inactive except as an occasional companion to the corresponding earth-god, who is usually female. While the sky-god becomes remote and virtually irrelevant, he is not forgotten. When times get tough and the very existence of the tribe, culture, nation, is in desperate jeopardy, all other measures have been tried without success, a group of believers will remember the remote, withdrawn sky god, and seek deliverance, forgiveness, mercy, etc.

The Religious Experience of Life The distancing of the sky-god may have a lot to do with the religious person's growing interest in religious, cultural & economic complexities as a culture evolves. People are distracted from the transcendent god in the sky. That god is remote and inactive, so it's no wonder the people focus on things that are more familiar, immediate, and seemingly relevant. As religious man discovers how sacred life is, he is seduced by his own discoveries, becoming preoccupied with what is close at hand, and perhaps less attentive to a vision of the world which is subtle, noble, all-encompassing, in every way "more spiritual," but less obvious, more difficult, more challenging, and exponentially more powerful.

Economy of the Sacred Just as a society has an economy of goods and services, religious life has its own economy. It has to do with the aspects of human existence, all of which are tied to a religious understanding of the world. And so religion becomes less abstract and removed, and more concrete and connected to life as it is lived. Other, lesser deities emerge, and they are more active and more accessible than the remote sky god who created the cosmos and then withdrew. Examples? People become preoccupied with corn or rain gods/spirits, which have much to do with the fertility, richness, fullness, and overpowering quality of life. And yet: "in an extremely critical situation, in which the very existence of the community is at stake, the divinities who in normal times ensure and exalt life are abandoned in favor of the supreme god." These "lesser" gods excel at reproducing and intensifying life. But they can't ensure a people's existence, or save them.

Perenniality of Celestial Symbols The gods in the sky never lose their dominant place in the "economy of the sacred." This is seen in patterns of religious behavior regarding the vertical dimension (think of the axis mundi, and images of climbing, ascending, etc.), and myth (stories related to the tree, mountain, ladder, like Moses at Sinai, Jacob at Bethel, Adam & Eve near the tree at Eden's center).

Structure of Aquatic Symbolism Think of the role rain plays in literature, art, movies, and twanging country songs. Shift perspectives. We've seen that water is given value by religious man (that's what valorization means). It disintegrates and abolishes what was, as such it is an agent of chaos. But water also acts as an agent of cosmos, in that it structures, purifies and regenerates -- think of the role water plays in the story of Noah. "The waters" symbolize possibility; out of water comes something new, re-created. Before there was anything else, there was water, according to the Creation story in culture after culture. Water benefits all things, as we will read in January. As we've seen, water stands for death but also, powerfully, for rebirth. Things touch water, and are regenerated. What used to be is dissolved. Something new is born. To be immersed in water is to cease to exist in one sense, to be absorbed back into something more elemental and primal, after which comes a new creation. Think of a person who, after much study and preparation, walks quietly with a group to a river, to be immersed in the flowing water, and to come up again. Think: before there was such a thing as Christianity, how interesting it is that a Jewish man named John the Baptist did this to an historical person, a Jewish man named Jesus.

Paradigmatic History of Baptism Baptism in Christianity reflects the universal pattern of water in religious life. Baptism suggests a connection with "sacred history," as when the waters, or the monsters in the water, were conquered. If you're interested, use a Bible Concordance and check out references to "Rahab" or "Leviathan." Look at old maps where explorers marked chaotic unknown territory with special effects-quality drawings of sea monsters. Baptism is an echo of the Flood and Noah -- destruction and re-emergence. It suggests a return to original innocence. The fact that water and baptism are universal paradigms reminds us that the connections among different peoples are deep and intense. Water, found in every tradition. A shimmering shape-shifting part of the pattern that connects.

Universality of Symbols Eliade is concerned with finding universal patterns and symbols, to which new layers of meaning are added as time marches on and religions are born and wither. As history moves along, the symbol survives, structurally intact. New meanings are attached. Some symbols, like some times and places, have a power that speaks to all humans in all times. The way they understand and articulate the power of that symbol may vary. Interested? Some day check out Carl Jung, Heinrich Zimmer, Joseph Campbell, many others. You're wondering, "Yes, but could we please have some examples, besides water?" And our friend Eliade is more than happy to oblige. Onward, campers.

Terra Mater "Mother Earth." This enormously

important idea is found everywhere in human history -- sometimes hidden,

camouflaged, buried, but never lost. It explains the feeling many people

have that they "belong" in a certain place. The recent phenomenon

of moving many times in a lifetime is relatively new and can seem bizarre

in the context of human history. To some it bespeaks a degree of alienation,

of disconnection from identity and place, of existential drift and chaotic

life patterns, part of what Eliade calls the "profane" mode

of being or way of living. For homo religiosus, the very rock

and soil of a location on earth seems to have a claim on us. The

claim is deeper than the strongest feelings for family and ancestors.

Think of what moving sometimes does to a family. To an individual. To

you, if you've left a place you loved, knowing that even if you return

it will not be the same.

Humi Positio Simply laying a newborn infant on the ground is a universal pattern reflecting the connections among the human mother, the newborn, & terra mater. It is seen in the universal custom of giving birth on the ground, or placing the newborn on the ground. Such physical contact with the earth allows the human mother to be guided in the mysterious act of giving birth, receive sustaining energy, and gain maternal protection. The "true mother" is earth, so an infant is placed on the ground as soon as it is born. Its "true Mother" legitimizes it, protects it, etc. The pattern, in slightly different form, is seen in the partial or complete burial of a person who is troubled or physically ill, who can be regenerated by contact with the earth Mother. Earth can play the same role as water.

Woman, Earth, and Fecundity So, the connection between women & the earth is big stuff. Agriculture arose & the religious view of women apparently changed. Matriarchy was common. Women, "owners" of the soil and crops, cultivated food. Human sexual behavior has as its model the relationship between the sky (male) and the earth (female); that relationship is sacred, cosmic, not to be taken lightly. Are there vestiges of this idea? Does it connect, or not, w/ feminism? Other trends?

Symbolism of the Cosmic Tree & of Vegetation Cults For homo religiosus, the appearance of life is the primary mystery of existence. Why is there life, instead of no life? Something, instead of nothing? The pattern emerges that something exists having to do with who we are, preceding our birth and following our death. Figuring out and responding to what that "something" is, is a primary concern of many traditions. Thus death is a threshold event, another aspect of human existence. The cosmos is a living organism which renews itself periodically (check James Lovelock's notion of Gaia and the idea of Earth-as-organism). The ability of life to re-appear even in the most difficult circumstances is stunning, pervasive, awe-inspiring. That ability is never exhausted; instead the wealth of species exuberantly reproducing is one of the most overwhelming aspects of existence. The idea finds a symbol with the tree, which stands for youth, life, immortality, wisdom. The tree often stands for what is most real, most sacred.

Desacralization of Nature The idea of nature as separate from

the Sacred is a recent phenomenon. Some contend that only a few people

even in modern industrial societies think this way completely. Even in

the most technologically obsessed, industrialized, secularized society,

the connection between the Sacred and nature is endures, if only in vestigial

form.

Review of Chapter 4, The Sacred & the Profane.

A religious person understands his life to be sanctified. That's the concluding point of Eliade in Ch. 4; it may not be as easy to get our arms around it as we think. Making his case, Eliade focuses on the people he knows best -- the peasants of Europe and by implication, the indigenous people of a particular place (paysan, paesano, peasant, etc.). Eliade is returning to his own roots to see how these folks understand their lives, the universe around them, and the meaning of being alive. His point can take a while to get a handle on. So, slow down.

* Is their understanding of, and form of, Christianity bigger & better than our understanding of it ? Their form absorbs much of the pre-Christian "cosmic religion," which includes the ideas in Ch. 3. They bring to Christianity a way of thinking and behaving that goes back so far it almost seems like it is in our genes. Thus their Christianity is close to the cosmic structure with which many modern Christians have lost touch. The social emphasis on technology (transportation, communications, etc.), industry, creation of false appetites (through advertising), speeding up of time ("Captain, the computer is just not....fast enough....time to upgrade....), and theological interpretations that encourage unfamiliarity with the elemental rhythmns that have served as organizational principles and guideposts for the overwhelming majority of human history (e.g., the seasons, the tides, the rotation of stars and sun and moon, the importance of spring and fall, of equinox and solstice).

* For these people, the existence of the world means something,

and that meaning can be communicated. The world is pregnant, in fact, not only

with the exuberant robust ever-present sense of fertility -- acorns

crunching under foot, seeds blowing by -- but bursting with meaning as

well. The amazing thing to such people is that modern folks (that's us) are

often illiterate regarding the text of creation -- deaf, dumb, and blind to

the real world all around us and what it signifies. And worse, indifferent

or smug regarding our own ignorance and narrow, cramped version of life. Eliade

suggests that the truest, oldest, religious impulse leads one to live with

a sense of wonder. The fact that there is life, instead of nothing, argues

that something big is at work here. Onward. As cultures evolve into greater

complexity, humans begin to see themselves as.....

* microcosms of the creation, and their lives as a

repetition of cosmic images and behavior. The world is the

original model, the archetype, the paradigm. This is what Eliade means

by homology. A homology (like the homology of earth & women)

is all about real life. It is to be experienced; it is

not abstract or purely conceptual. Thus, of course our lives are more

than they appear to be, homo religiosus might say. If we are

open to the world, according to homo religiosus, we see this.

And the acute and peculiarly modern epidemic of loneliness is no longer

a common problem, because there is always companionship, walking

through such a lively creation, with lots of company on the "outside," and

with the knowledge that so much is inside us. The poet Gary Snyder

mentions our many companions, and the compacts among us -- salmon

swimming to visit the human beings, to be entertained by their singing

and dancing and the shadows thrown by firelight, to be killed, shed

of the silvery skin, freed from that existence, energy transforming.

* this way of seeing life costs nothing, Eliade

implies; or we might infer that it costs what is in fact without value

anyway. Instead, it adds to life. Things we have, things we

do, ideas we think, words we say and feelings that are evoked within

us by the most unexpected things all have their obvious meaning and

value. Being open and receptive, drinking it all in unfiltered, we

come to know the marvelous world we inherited. In gaining that knowledge

we come to know ourselves. Such knowledge as so precious that it is,

literally, beyond words. Onward.

Sanctification of Life Important experiences -- eating, work, play, breathing,

walking, sex, etc. -- have no greater meaning for modern, non-religious

people, Eliade contends. They are what they seem to be on surface -- simple

physiological acts. At the extreme they reflect greedy, lazy, undisciplined,

addicted minds. In contrast, for many religious people the most minute aspects

of human existence have spiritual import and value. For such a person life

has two planes: the "merely human," and its model, the cosmic. [Refer

to Wendy Doniger's interview/essay handout, and how living with both worlds

in mind is doubly sustaining.] We find an enormous number of homologies between

humans and creation in culture after culture. Examples? At the most obvious

level, Eye/Sun. Two eyes/Sun & moon. Cranium/Full moon, or celestial vault.

Breath/Wind. Bones/Stones. Hair/Grass. Womb/Cave. Intestines/Maze. Breathing/

Weaving. Spine/Axis mundi. Navel/Center. These homologies regarding

humans and creation represent real (existential) situations. The connections

drawn between the individual and the entire creation vary from culture to culture.

The larger pattern is almost always there. This suggests that there are an

infinite number of experiences available to homo religiosus, because

such a person makes himself accessible. The seemingly mundane experiences are

....cosmic. They must be in some sense religious experiences, because

the cosmos itself is sacred and we are a part of it. Thus the primary physical

things we do become sacraments. Eating. Marriage. Work. Breathing. Walking.

All potentially powerful activities seen from a spiritual perspective. A related

set of behaviors can develop around them -- a ritual. In highly evolved traditions,

they can be seen as powerful techniques which transport the practitioner to

a state of mind that is more aware, more accessible.

Body-House-Cosmos Homo religiosus is in communication

with the Sacred, and shares in the sanctity of the world. One logical

result is that he cosmicizes himself, in recognition

of the parallels between his body, house, and cosmos. A homology.

Spine=axis mundi. Breath=Wind. Navel or heart = Center of the World.

Openings in the body = Doors. At each level (body, house, cosmos) the vertical

opening up is all-important. The upper opening allows passage to

another world. (pg. 174-175, and the many images of breaking away,

upward, shattering the roof, and flight). A person becomes a complete

microcosm of Creation, as an object and actor, creating as well

as simply being. One idea: where we live represents our

place, status, state of mind, in the cosmos. So the image of breaking

free, upward, through the roof or skull or sky, is a radical step toward

absolute freedom, wiping out the possibility of a conditioned, familiar,

mundane world. Of course, none of this applies to the secular ("profane")

person, for whom the world is static, opaque, with no message and no

communication. E. suggests Christians who live in industrial societies,

and intellectuals, are in this category. They've lost the cosmic values,

and their spiritual experience is far less than it could be; it is

completely private (between them and God) and focused on salvation.

He suggests that this is a compromised way to live.

Passing Through the Narrow Gate The key idea here is the importance

of changing, of becoming -- perhaps we are not complete at birth,

but must be born spiritually as well. Thus the emphasis on passage,

which can also be understood as initiation, another kind of threshold.

Through a series of passages we become complete. The passage

is almost always upward, signifying transcendence. Without such

initiations we can remain unformed, imperfect, embryonic, all potential and virtual,

nothing actualized or formal. Think: adults who act like

children. What did they miss? Paul the Apostle writing about having

to put away childish things. What did he experience? The opening upward

allows passage from one "mode of being" to another, e.g.,

from the profane to the sacred, from who we were to who we become.

The threshold marks the boundary and provides the possibility of movement.

Among the most common images are the bridge and the narrow

gate, and the images often involved danger. Think: Jesus remarking

on a how difficult it is to pass through the eye of a needle, and how

difficult for a rich person to enter the Kingdom. Have we ever tried

to change something about ourselves? Magnify it. Imagine being initiated

into a special group. Or death as a passage to the next stage. Understanding

something or someone deeply for the first time. Really walking

in someone else's shoes. Not making critical assumptions about

people because we've come to understand how little we know about

their situations. Small passages and big passages.

Rites of Passage Homo religiosus wants to be different

from what he is, on the "natural" level. He wants to make

himself into something else, taking an ideal model as the example,

and embarks on the task. Religious people do things -- rites

-- when they are making such a passage -- at birth, baptism, marriage,

death, etc.. The importance of ceremony -- graduation, for example. "The

primitive," man becomes complete when what he was ceases to be.

This idea of initiation, or passage, survives for the non-religious.

It's a pattern of human behavior even among the non-religious, but desacralized --

hollow compared to the experience religious people enjoy, E. suggests.

Phenomenology of Initiation Eliade contends the initiation is

the equivalent of spiritual maturing. Once initiated, one knows.

The true dimensions of existence are revealed to the novice. One is

introduced to the Sacred, and becomes responsible for being a woman

or man.

Death and Initiation Note that Eliade says "primitive man" has

sought to conquer death by transforming it into a rite of passage.

Death involves something temporary -- profane life -- and is

the supreme initiation into what is permanent and absolutely essential,

a new spiritual existence.

"Second Birth" and Spiritual Generation Sacred knowledge

and wisdom are won through initiation. New values are grasped.

Old ones are left behind. One dies to the profane condition, having

earned access to spiritual life through a second birth.

Sacred and Profane in the Modern World Religious people believe

in an absolute transcendent reality, manifesting itself in this world,

sanctifying it and making it real. Thus life is sacred in origin and

our existence realizes all of its potential to the degree that it

participates in reality -- or, is religious. Non-religious man

refuses transcendence, sees reality as relative, and may doubt the

meaning of existence. Such a person sees himself as what history

is about and what makes history. There is no appeal to transcendence.

He assumes a tragic existence. But he is the result of a process

of desacralization. His life was formed by opposing homo

religiosus, of trying to empty himself of all religion and

all meaning that is more than human. He can be seen to hold to "pseudo-religions" and degenerated

mythologies. In contrast, for religious man the solutions to

every crisis can be found. Models -- paradigms -- instruct and

inform. The values empower us to transcend personal situations and

gain access to the spiritual. Symbols give our experiences depth

and meaning. Experiences become spiritual acts, and foster a spiritual

understanding of the world. Symbols can lead us out of a situation

and open our eyes to the general & universal. E. says that for

non-religious people religion is "in eclipse" -- think

of the literal image, of the sun covered by a shadow, but still there.

They can reclaim the religious vision, reintegrate what they are with

something beyond the superficial and familiar. A memory remains of

how things really are; it can be rediscovered, enabling them to see

clearly the traces of something unimaginable, creative, dynamic, overwhelming,

at work in the world.